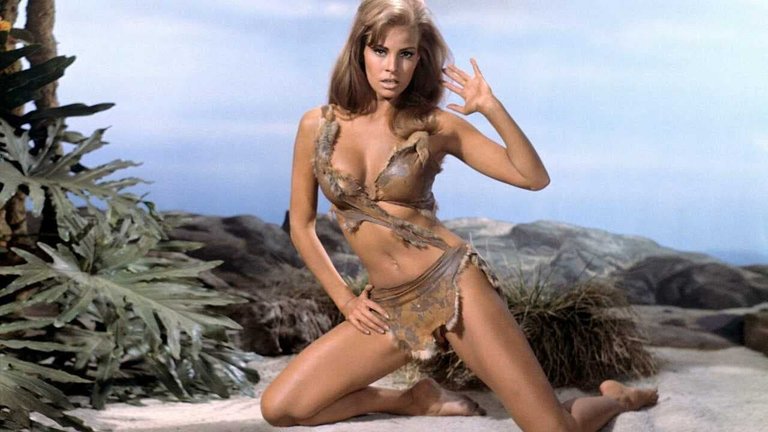

Certain films that once captivated audiences now seem to crumble under the weight of critical scrutiny, their reputations sustained not by artistic merit but by a confluence of cultural timing and exploitation. One Million Years B.C., a 1966 pseudohistorical adventure directed by Don Chaffey, epitomises this phenomenon. Produced by Hammer Film Productions—the British studio renowned for its lurid, stylish horror films of the 1950s and 1960s—this remake of the 1940 black-and-white classic of the same name thrived on a blend of primal spectacle and calculated provocation. While its plot and execution may strike modern viewers as simplistic or anachronistic, the film’s enduring cultural footprint lies in its ability to capitalise on the era’s fascination with prehistory, enhanced by a marketing blitz that turned Raquel Welch’s controversial “fur bikini” into a pop culture landmark. For all its flaws, One Million Years B.C. remains a curio of its time, a product of exploitation aesthetics and the studio’s knack for leveraging controversy into longevity.

Hammer Film Productions, synonymous with Gothic horror and lurid camp, ventured into prehistoric terrain with One Million Years B.C., a colour remake of the 1940 film. Screenwriter and producer Michael Carreras’ script retained the original’s broad strokes but shed its framing device—a modern-day paleontologist’s prologue—opting instead for a straightforward opening narration. The story unfolds in a brutal primordial landscape where rival tribes, the violent Rock People and the pacifist Shell People, vie for survival amid predatory dinosaurs and environmental hazards. John Richardson stars as Tumak, the Rock People’s rebellious heir, whose banishment sparks a journey to the Shell People, which include resourceful Loana (Raquel Welch). Their uneasy alliance culminates in a showdown between tribal ideologies, interrupted by a volcanic cataclysm. While the plot is rudimentary, it provides a canvas for Hammer’s trademark mix of exploitation and spectacle, balancing anthropological speculation with visceral action.

Carreras’ initial ambition to remake King Kong was thwarted, leading him to settle on One Million Years B.C., a choice that inadvertently aligned with Ray Harryhausen’s expertise in stop-motion animation. Harryhausen, renowned for his work on Jason and the Argonauts (1963), lent his craftsmanship to the film’s creatures, blending practical effects with nods to the 1940 original—such as scaling lizards to appear colossal. Though the dinosaurs and other monsters (including a grotesque giant spider) adhere to mid-1960s technical standards, their inclusion drew ire from paleontologists, as the film’s title inaccurately places humans alongside dinosaurs. Harryhausen’s creations, however, were recycled in later films, ensuring his influence outlived the project’s scientific inaccuracies.

Beyond Harryhausen’s creatures, the film’s visual allure stems from its Canary Islands locations, shot in winter to evoke a harsh, prehistoric environment. Chaffey’s direction heightens the setting’s desolation, contrasting the Rock People’s rugged terrain with the Shell People’s verdant oasis. This stark geography underscores the narrative’s themes of cultural clash, with the environment itself serving as a character. The decision to film on location, rather than rely on studio sets, grants the film a tactile authenticity that elevates it above typical studio-bound B-movies.

The script attempts a speculative glimpse into prehistoric life, albeit with glaring anachronisms. While the Rock People’s violent tribalism and the Shell People’s egalitarian gatherer society offer a simplistic dichotomy, the film’s strongest moments lie in its depiction of evolving culture. The Shell People’s invented language—a melodic, guttural dialect—contrasts with the Rock People’s grunts, suggesting early linguistic development. Similarly, the inclusion of tools hints at technological progress, albeit placed hundreds of millennia too early. Yet these attempts at authenticity are undercut by exploitation tropes: the Rock People’s ritualistic violence and the Shell People’s near-nudity lean into 1960s exoticism, reducing prehistory to a canvas for primal instincts.

The film’s most notorious element is its marketing, which sensationalised Welch’s costume—a leather garment erroneously dubbed a “fur bikini.” This imagery became its calling card, attracting audiences with promises of sex and spectacle. Inside, the script delivers on exploitation: Loana’s fight with Nupondi (Martine Beswick), a rival for Tumak’s affection, features brutal, unglamorous violence, while scenes of tribal warfare and animal attacks court controversy. These elements led to censorship battles, particularly in the U.S., where edits diluted the film’s impact. Today, such content feels tame, yet its historical notoriety underscores Hammer’s willingness to push boundaries for profit.

Despite its strengths, the film is hampered by Mario Nascimbene’s intrusive score, which bombards scenes with bombastic orchestral swells and tribal drumming. While intended to heighten tension, the music often overwhelms the narrative, rendering dialogue inaudible and the environment less immersive. This soundtrack now feels jarringly incongruous, distracting from the film’s otherwise atmospheric visuals.

One Million Years B.C.’s commercial success propelled Welch into stardom, cementing her as a 1960s sex symbol. Hammer capitalised on the film’s popularity with three spiritual sequels—Prehistoric Women (1966), When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth (1970), and Creatures the World Forgot (1971)—each recycling the formula of giant monsters and scantily clad heroines. Though these films lacked the original’s impact, they solidified Hammer’s reputation for lowbrow spectacle, catering to audiences craving primal thrills.

The film’s most unexpected claim to cinematic immortality emerged decades later in The Shawshank Redemption (1994), where the iconic poster of Welch’s character adorns a prison cell. While this subtle nod is a minor detail, it underscores the lingering presence of One Million Years B.C. in pop culture consciousness—a relic that, for better or worse, refuses to be forgotten.

One Million Years B.C. is a product of its time: a messy, exploitative adventure that thrives on spectacle over substance. Its scientific inaccuracies, clunky dialogue, and intrusive score mark it as a relic of 1960s exploitation cinema. Yet its cultural resonance endures, thanks to Welch’s enduring mystique, Harryhausen’s stop-motion ingenuity, and the era’s fascination with prehistory. For all its flaws, the film remains a testament to Hammer’s ability to turn low-budget thrills into cult classics—a reminder that iconography often owes as much to marketing as to artistic vision.

RATING: 6/10 (++)

Blog in Croatian https://draxblog.com

Blog in English https://draxreview.wordpress.com/

InLeo blog https://inleo.io/@drax.leo

Hiveonboard: https://hiveonboard.com?ref=drax

InLeo: https://inleo.io/signup?referral=drax.leo

Rising Star game: https://www.risingstargame.com?referrer=drax

1Inch: https://1inch.exchange/#/r/0x83823d8CCB74F828148258BB4457642124b1328e

BTC donations: 1EWxiMiP6iiG9rger3NuUSd6HByaxQWafG

ETH donations: 0xB305F144323b99e6f8b1d66f5D7DE78B498C32A7

BCH donations: qpvxw0jax79lhmvlgcldkzpqanf03r9cjv8y6gtmk9