In the annals of cinema, the ascendancy of feature-length films in the early 20th century relegated short films to the periphery, often dismissed as mere curiosities or stepping stones for aspiring auteurs. To transcend this marginalisation, a short film had to possess extraordinary artistry or universal resonance. Albert Lamorisse’s The Red Balloon (1956), a 34-minute French fantasy, achieves precisely this, carving its place as one of the few shorts to attain enduring acclaim. A poetic blend of childlike wonder and visual allegory, the film defies its brevity, offering a meditation on loneliness, innocence, and imagination that continues to captivate audiences nearly seven decades later. Yet, while undeniably a classic, its flaws—often glossed over in nostalgic retrospectives—reveal the limitations of its minimalist approach.

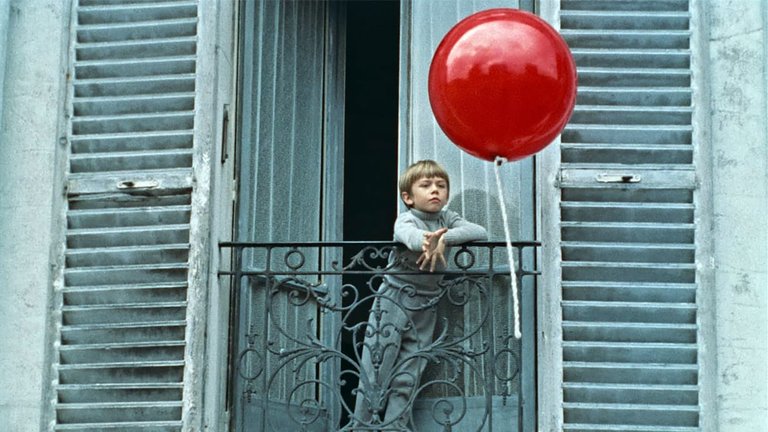

Lamorisse’s film, a hybrid of fantasy and adventure cloaked in the guise of a children’s story, unfolds in the working-class Ménilmontant quarter of 1950s Paris. Pascal (played by the director’s son, Pascal Lamorisse), a solitary schoolboy, discovers a sentient red balloon that becomes his whimsical companion. The balloon—vibrant against the drab greys of the cobblestone streets—follows him like a loyal pet, dodging bullies and flitting through courtyards with a life of its own. Their idyll is shattered, however, by a gang of envious boys who destroy the balloon in a scene of startling violence, only for the film to conclude with a surreal catharsis: a flock of balloons whisking Pascal skyward over Paris. This bittersweet denouement, balancing tragedy with transcendence, encapsulates the film’s duality—a fable as much about cruelty as it is about hope.

The Red Balloon’s power lies in its narrative economy. Lamorisse, who earned the Academy Award for Best Original Screenplay—the only short film to do so—eschews dialogue almost entirely, relying on visual storytelling to evoke emotion. Critics have projected myriad interpretations onto this sparsity: Pascal as a social outcast finding solace in an imaginary friend, the balloon as a Christ-like martyr sacrificing itself for his redemption, or even an allegory for post-war resilience in France. Such readings, while compelling, risk overcomplicating a film whose magic derives from its simplicity. Lamorisse invites viewers to project their own meanings, yet this very openness can feel like an evasion—a refusal to commit to emotional depth. The boy’s relationship with the balloon, while charming, remains superficial, its abrupt destruction more aesthetic than affecting.

The film’s accessibility made it a staple in global classrooms from the 1960s to 1980s, particularly before colour television’s ubiquity. Educators praised its wordless narrative, which transcended language barriers, and its vivid imagery, which kindled young imaginations. Cinematographer Edmond Séchan’s palette—muted greys and blues punctuated by the balloon’s scarlet brilliance—transforms Ménilmontant into a liminal space between reality and fantasy. Maurice Le Roux’s score, alternately whimsical and melancholic, heightens this ethereal quality, though its occasional sentimentality veers perilously close to cliché.

For contemporary audiences, the film’s documentary value rivals its artistic merits. Lamorisse’s lens preserves Ménilmontant’s labyrinthine streets and weathered tenements—a world obliterated by 1960s urban renewal. The quartier’s demolition lends the film an unintended poignancy; Pascal’s adventures unfold in a Paris now lost to modernity. This historical resonance, however, is incidental rather than intentional, a byproduct of the director’s focus on allegory over realism.

The film’s weaknesses emerge most glaringly in its emotional core. Young Pascal’s performance, while endearing, lacks nuance—a limitation Lamorisse masks by avoiding close-ups and privileging the balloon as the true protagonist. The decision to omit Pascal’s reaction to the balloon’s destruction feels particularly jarring; we see neither tears nor resolution, only a swift cut to the fantastical finale. This elision, perhaps intended to universalise grief, instead renders the loss abstract, diluting its impact.

The Red Balloon remains Lamorisse’s magnum opus, though his career—cut short by a fatal helicopter crash in 1970 while filming The Lover’s Wind—hinted at broader ambitions. Best known outside cinephile circles as the inventor of the board game Risk, Lamorisse blended a game designer’s grasp of narrative stakes with a poet’s eye for imagery. Yet his filmography, including the similarly lyrical White Mane (1953), often privileged aesthetic harmony over character development—a trade-off that leaves The Red Balloon feeling more like a beautiful artifact than a deeply human story.

The Red Balloon is not merely as a children’s film but as a testament to cinema’s ability to conjure wonder from simplicity. Its flaws—emotional reticence, underdeveloped protagonist—are outweighed by its visual innovation and allegorical richness. Yet to hail it as flawless is to ignore its missed opportunities; the film’s reluctance to deal with Pascal’s inner world leaves its most poignant moments feeling unearned. Lamorisse’s masterpiece remains a balloon itself: luminous, buoyant, and tantalisingly out of reach.

RATING: 8/10 (+++)

Blog in Croatian https://draxblog.com

Blog in English https://draxreview.wordpress.com/

InLeo blog https://inleo.io/@drax.leo

Hiveonboard: https://hiveonboard.com?ref=drax

InLeo: https://inleo.io/signup?referral=drax.leo

Rising Star game: https://www.risingstargame.com?referrer=drax

1Inch: https://1inch.exchange/#/r/0x83823d8CCB74F828148258BB4457642124b1328e

BTC donations: 1EWxiMiP6iiG9rger3NuUSd6HByaxQWafG

ETH donations: 0xB305F144323b99e6f8b1d66f5D7DE78B498C32A7

BCH donations: qpvxw0jax79lhmvlgcldkzpqanf03r9cjv8y6gtmk9